|

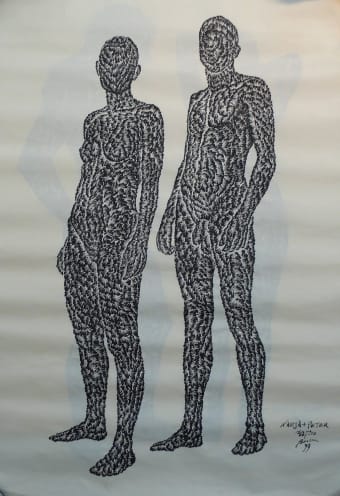

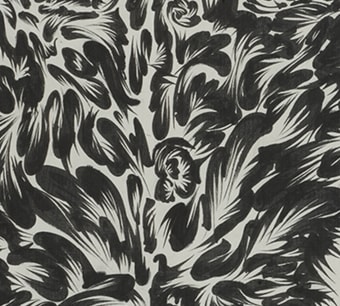

Starting with his Lover's Library series of 1998, Huang Zhiyang explores the inter-subjective world of human relationships as seen through the virtue of love. In earlier works from the series, Huang depicts couples he met in New York and Hong Kong as two naked figures standing in personal relation to one another (fig. 1). Although usually a man and a woman, Huang sometimes depicts two women or two men together. The two subjects are often lovers but sometimes the postures denote some other relation such as friendship or kinship. At first, the subjects appear to us in silhouette. Upon closer inspection, however, one perceives first pattern and then detailed surface form (fig. 2). Like the texture strokes used in classical landscape painting to depict mountains and rocks, Huang uses his brush vocabulary of cohering 阴 yin and expanding 阳 yang strokes to render the living surface contours of his human subjects.

In his latest works for Beijing Lover's Library, Huang changes his visual vocabulary to reflect a broader, Confucian notion of love.

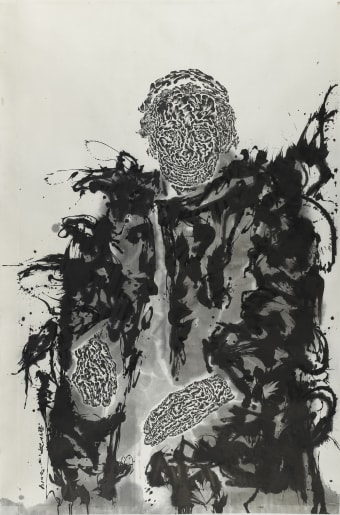

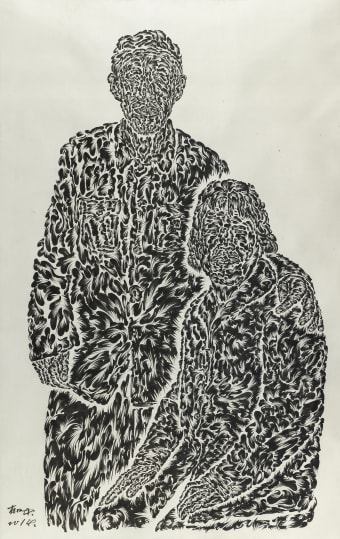

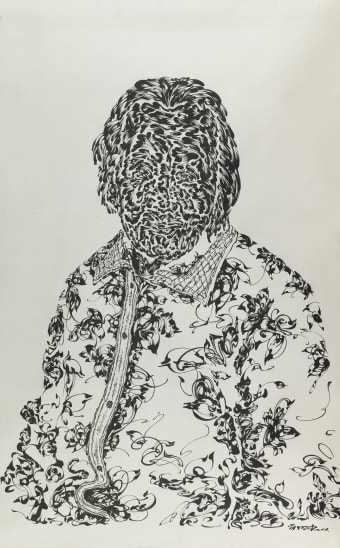

In Confucius' own formulation, 仁 ren or "humanity," defines what it means to be human or humane. Composed of two component characters ("person" [人 ren] and"two" [二 er]), it represents how two people feel and act towards one another. For Confucius (551-479 BCE), ren is to feel for others as one feels for oneself; it is to empathize with others or, simply, to love others. To express this notion of ren, Huang usually depicts two figures in empathetic relation to one another. For Beijing Lover's Library, however, Huang includes solo portraits, too (fig. 3). Sitting for a portrait without lover, family or friends, this elderly woman's loneliness is palpable to anyone with a moment to reflect. In evoking this feeling, Huang finds in all of us the capacity to feel for her and with her. 老吾老以及人之老 lao wu lao yiji ren zhi lao, "to feel towards all elders as one would towards one's own," (Mencius, c. 372-289 BCE), this is ren. In addition to ren, Confucius describes two other moral virtues that are foundational to human society and civilization. 义 yi or "justice" is the sense as well as the pursuit of right over wrong, of fairness and rightness in one's own actions and within society as a whole. When human beings empathize with one another, we can't help but feel a sense of what is right, fair or just not only in regards to ourselves but in regards to others. When we abide by what we feel is fair to everyone, this is yi. This is the basis in moral feeling for collective social action. By depicting the portrait of an elderly loving couple from a remote farming village in Our First Portrait Together, Huang proclaims that regardless of ethnicity, religion, wealth or social position, all are equal under the dignity of love (fig. 4). This sense of equal dignity is yi. 礼 li or "propriety" defines the social norms by which people outwardly express their humanity and right action to one other and is variously translated as "ceremony," "rite," "ritual," "etiquette," or "manners." Propriety is meaningless when not motivated by the corresponding inward feelings that underly its form. On the other hand, when inward feeling and proper social form come together, feelings are communicated and shared intuitively and completely between individuals and within groups. When Huang depicts his elderly subjects not naked and standing exposed but clothed and seating for a formal portrait, he shows us the norms by which people express their identities within Chinese society today (fig. 5). This formal, performative aspect of human feeling and social action is li. In Song dynasty (960-1279) neo-Confucianism, these moral feelings are not separate from the natural world we live in but rather an extension of it. Just as the rules of chemistry bond atoms to form molecules, metabolic chemistry organizes molecules in autopoeitic cellular networks, genes direct cells to form organ systems and organisms, and evolution enables organisms to form species within larger ecosystems, the inter-subjective moral nature of human individuals enables the human species to form families, communities, societies and civilizations. It is the next step in the same evolving process of unfolding order and complexification that produced humanity from consciousness, consciousness from life, life from matter and matter from energy.

The modern sciences — energy physics, stellar and planetary astro-physics, geology, non-linear dynamics, chaos and complexity theory, pre-biotic evolution, metabolic chemistry, microbiology, evolutionary biology, deep ecology, neurology and phenomenology — achieve a semblance of this unified unfolding through novel concepts such as emergence — the idea that order arises naturally and spontaneously from non-linear systems of matter and energy. Song daoxue, however, is unique in providing not only perspective on the unfolding structure of natural order but the methods and means to use this insight in one's personal life — particularly one's relationship to a larger society and to a greater natural world.

Zhu Xi's朱熹 (1130-1200) 理学 Lixue — or the empirical study of order (li) as exhibited by the external world (i.e. nature and society) — and Wang Yangming's王阳明 (1472-1529)心学 Xinxue — or the phenomenological (i.e. subjective) study of order as reflected in the mind (心 xin) — are two of the methods developed by the neo-Confucians to systematize this kind of personal cultivation. A third method, however, predates either of these and traces its origins to a time before even Confucius when the primary means of self-cultivation was the arts — or the aesthetic coupling of patterns of order inherent in one's mind with those immanent in nature.

In a nutshell, this is what Huang means by 工 . 课 gong . ke: art becomes a vehicle for self cultivation whereby one's mind both shapes and is shaped by a world in which it is co-emergent through the resonance of order immanent in each. If you are Confucian, this kind of personal cultivation is the only way in which an individual can actually lead a society and thereby change the world. The moral knowledge that leads to action and change does not come from information, analysis and logic; rather, it comes from direct experience, training and practice — it is itself an art. |

Huang Zhiyang: Lover’s Library

Craig Yee