New York | Every One Every Where Every When: Li Jin and the Art of the Portrait

Ukrainian Institute of America

2 E 79th Street

New York, NY 10075

Eat, Drink, Man, Woman

Li Jin (b. 1958 in Tianjin, China) is perhaps best known for his lush and colorful chihenannü "Eat Drink Man Woman” series depictions of sensory pleasures in contemporary China. In his banquet scenes and anecdotal vignettes, voluptuous men and women are surrounded with food in various states of undress and sexual intimacy. Often portraits of the artist himself, the figures suggest both playful self-amusement and reflective distance. Indeed, even at their most extravagant, Li Jin's pleasures scenes are tinged with the melancholy of solitude and the unreality of a dream or a memory.

In truth, Li Jin's art has always had a spiritual undertone, perhaps even a spiritual purpose. In 1984, inspired by the examples of van Gogh and Gauguin, he went to Tibet in search of an authentic life and primal connection to nature. There, particularly after witnessing a sky burial, he began to reflect on the limits of corporeal existence. Drawn to the religiosity and the sense of time and history in Tibetan culture, he would sojourn twice again in the region, but would gradually come to recognize its essential alien-ness from himself.

Upon leaving Tibet in 1993, he set out to embrace the shifting realities of contemporary China under liberalization. Inspired by his new life in a Beijing hutong, he developed an aesthetics of xianhuo, or "aliveness." His paintings came to represent food, sex, and other aspects of quotidian life with honesty and enthusiasm, and in a manner strongly evoking first-hand experience. As he gained in reputation and exposure, his paintings also changed, becoming increasingly boisterous and incorporating experiences of his travels abroad.

Li Jin’s Portraits

Central to Li Jin’s overall artistic practice is the art of portraiture. Although long associated with the art of the landscape, Chinese painting begins, in the Han Dynasty (202 B.C.E. to 220 C.E.) and even earlier by textual accounts, with figure painting as a means of moral instruction. As soon as the Six Dynasties (220–589) when the birth of the extraordinary artistic persona first gave rise to calligraphy, poetry, music and painting as expressive fine art forms, portraiture arose as the visual art that best captured the extraordinary individual personas of the day. Gu Kaizhi (c. 344–406), the greatest painter of this period, was famed for his portraiture and Xie He (fl. 6th century), the author of Huihua Liu Fa or the “Six Laws of Chinese Painting”—China’s earliest theory of painting aesthetics—was himself a portrait painter.

In the Chinese art of portraiture, the prime disiderata of painting is chuanshen or “to transmit the spirit” of your subject or sitter. In fact, one can thinking of the rest of Xie He’s Six Laws as simply the means to achieving the result of chuanshen. In this formulation, the extraordinary subject was the sitter and not the portrait artist—the artist’s goal was not to transmit his own spirit but to transmit that of his subject. In this light, one can think of Li Jin’s practice of self-portraiture as a present-day re-affirmation of the artist as the extraordinary subject while simultaneously returning to the human figure and to portraiture as the means of chuanshen—transmitting his or her artist’s spirit.

The Heart Sutra

In The Heart Sutra, Li Jin presents us with one of his fantastic, imaginary banquet scenes. This time, however, his primary mode of painting is not the traditional figure but the portrait. His list of subjects include historical celebrities such as German social theorist Max Weber, James Bond actor Sean Connery and Ramones drummer Marky Ramone; real people Li Jin has encountered in the streets of Osaka, New York and Berlin; people and animals sporting a variety of masks including those of plague physicians during Europe’s Black Death, oxygen respirators of aviators from World Wars I and II, masks for animals particularly dogs and pigs, and perhaps even masks for S&M role play; and finally no less than eight portraits of the artist himself as Norman soldier, Elizabethan tradesman, Brooklyn hipster, befuddled ski accident victim, disgruntled artist, and Edwardian chauffeur amongst others.

In front of the assembled diners, Li Jin depicts an unending bounty of exotic delicacies such as chicken heads and feet, boar’s head and fresh eel, grubs and caterpillars; banquet favorites such as lobster, whole fish, sushi, fat pork and 110-proof, distilled Maotai liquor; and everyday favorites such as boiled dumplings, frog’s legs, hot dogs, bok choy and radishes. Throughout this unfolding indulgence, however, Li Jin inscribes his painting with texts from the Buddhist liturgy: the Repentance Master Cíyún's Pure Land Verses, the Compassionate Repentance of Emperor Liang, the eponymous Heart Sutra, the Eight Verses in Praise of Maitreya, and the Compassionate Samadhi Water Repentance, amongst others. Chanting these texts or writing them as Li Jin does here, is an act of repentance—a means of accumulating merit to counterbalance a life of ongoing attachment and sin.

Indeed, at the center of the composition is the headless, Willendorf-proportioned torso of a female figure. Unabashedly ample bodies are a recurring theme in Li Jin’s painting and convey the inescapable corporeal nature of human existence and its incumbent pleasures and desires. Here, it serves both as a celebration of the body and its power to give life and as a very personal confession to the desire such bodies evoke. As New York-based writer and critic Jeffrey Hantover once observed, “Li Jin’s battle between indulgence and moderation—the devil and monk within him—and self and selflessness is constant. Great art comes from conflict, internal and external—the law versus natural morality in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn … or the personal battle with addiction and despair in O’Neil’s Long Day’s Journey into Night. Whether Li Jin wins or loses the fight, we the viewers of his most human and affecting art continue to be the winners.”

Portraits from Daily Life

For Li Jin, painting and living are inseparable and indeed one mode of his artistic practice involves daily studies of his lived experience, particularly when he is traveling. In this mode, Li Jin inflects his traditional figure painting and portraiture with the Socialist Realism that every artist in Communist China learns in the course of his or her art education. Li Jin’s Socialist Realism, however, is not part of a larger social or political agenda but is, rather, strictly personal.

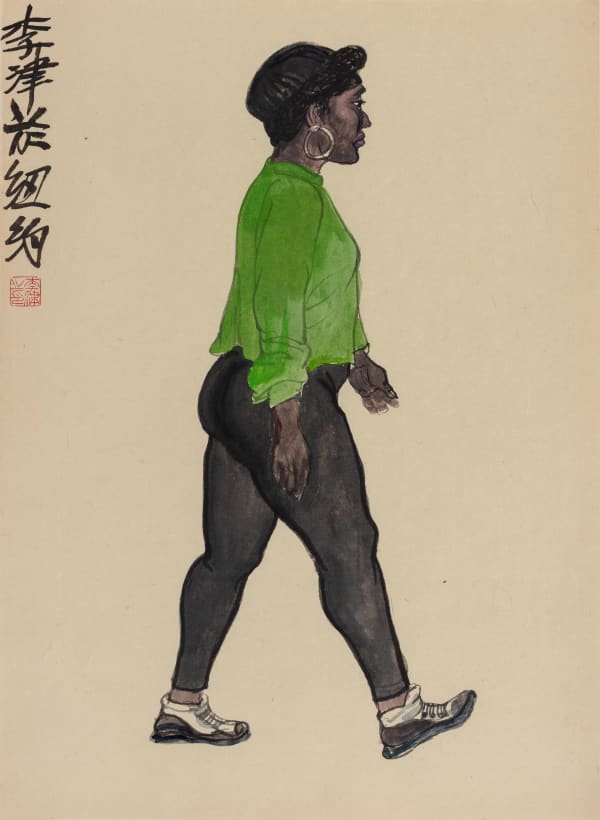

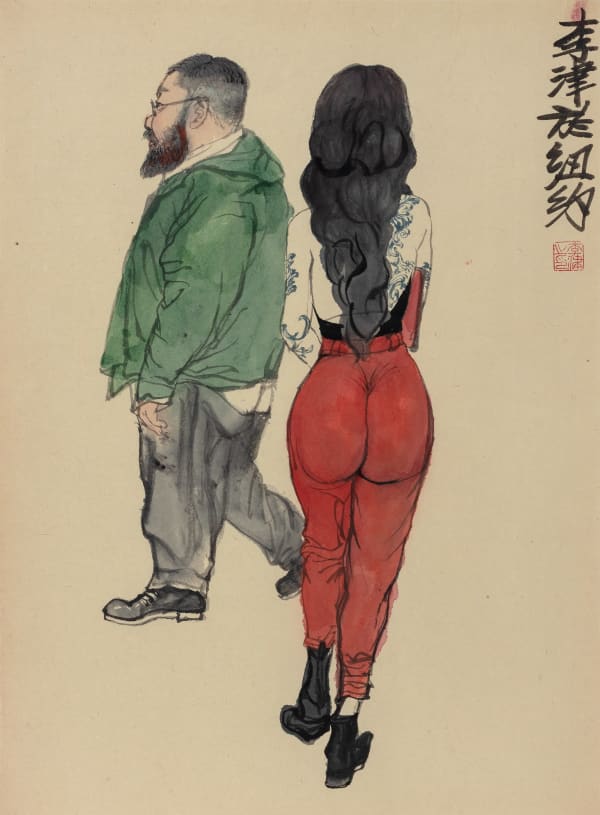

In his Morning Exercise in New York series, Li Jin documents his morning excursions during his month-long stay in New York in the Fall of 2019. In number IV of the series, Li Jin combines traditional portraiture with his art school training in Socialist Realism to sketch a young woman standing perhaps at a cross-walk. As he frequently does in his figure painting, Li Jin includes himself in the composition turning this into a self-portrait with an anonymous stranger. As with many of Li Jin’s morning exercises, his subject is observed from a distance, here from behind. The artist must thus tell the story of this young woman—and by extension his own story—using nothing more than body posture. In number VII of the series, Li Jin is clearly captivated by a young, African-American woman. He deftly employs the tools of traditional portraiture—namely achieving a “resonance with his subject’s energy” and capturing the “bone structure” of his subject’s figure—to chuanshen “transmit the spirit” of his anonymous admiration. Li Jin adds himself in the background observing his subject from a distance while she herself appears innocent of his interested gaze. Finally, in Good Artists, Li Jin documents his excursion to the New York Guggenheim. In this scene, an athletic young woman and a uniformed and bespectacled security guard—both clad in black—engage in conversation while an unshaven man sporting blue jeans, Nike high-tops and a windbreaker peers through his sunglasses as this encounter unfolds. Is he watching the conversation or is he checking out the young lady or is he, perhaps, looking at us the viewer? We ask ourselves: Are they artists? And if so, are they “good artists”? Or are the good artists in the exhibition and by exclusion the rest of us are just not so good artists?

In his Floating Rainbow series, Li Jin documents his experience joining the Los Angeles Pride Parade and Festival during the Summer of 2017. In No. 1 of the series, a bearded, somewhat paunchy gay couple with matching red tank-tops stride past. In the background a revealingly clad leather cowboy looks away while two women rendered in polychrome pastels watch, like us, the scene unfold before them. Li Jin clearly delights in the festive joy, colorful freedom of expression, and unabashed display of flesh—all recurrent themes in his traditional figure paintings of contemporary China—only this time found half way across the world at LA Pride. In No. 2 of the series, a young European-American man holding a camera and older African-American women holding a sign with the word “Resistance” walk together. Li Jin must have liked this scene because he paints himself into the composition as the onlooker in a blue and green shirt and fuchsia dog-eared cap. LA’s Pride Parade and Festival is a community gathering of people celebrating diversity and individuality. At the same time, it is public forum for political action and mobilization. For LGBTQ+ communities in the United States, community celebration and political mobilization are inseparable aspects of an ongoing social movement and Li Jin looks on with genuine excitement and admiration.

Li Jin’s diaristic studies are, on the one hand, Socialist Realist portraits of the individuals and communities that he encounters in his daily life. However, by chuanshen “transmitting the spirit” of the peoples and lives Li Jin encounters, he in turn transmits to us the spirit of his own extraordinary life. As in China’s bygone past, the artists of our time are the extraordinary personas and in Li Jin’s case, it is through the figure and the portrait that he shares with us his own extraordinary spirit.

-

Li Jin 李津, The Heart Sutra 心经, 2020

Li Jin 李津, The Heart Sutra 心经, 2020 -

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课Ⅰ Morning Exercise in New York I, 2019

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课Ⅰ Morning Exercise in New York I, 2019 -

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课Ⅱ Morning Exercise in New York II, 2019

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课Ⅱ Morning Exercise in New York II, 2019 -

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课Ⅲ Morning Exercise in New York III, 2019

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课Ⅲ Morning Exercise in New York III, 2019 -

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课Ⅳ Morning Exercise in New York IV, 2019

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课Ⅳ Morning Exercise in New York IV, 2019 -

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课Ⅸ Morning Exercise in New York IX, 2019

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课Ⅸ Morning Exercise in New York IX, 2019 -

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课Ⅵ Morning Exercise in New York VI, 2019

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课Ⅵ Morning Exercise in New York VI, 2019 -

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课Ⅶ Morning Exercise in New York VII, 2019

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课Ⅶ Morning Exercise in New York VII, 2019 -

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课Ⅷ Morning Exercise in New York VIII, 2019

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课Ⅷ Morning Exercise in New York VIII, 2019 -

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课Ⅹ Morning Exercise in New York X, 2019

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课Ⅹ Morning Exercise in New York X, 2019 -

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课Ⅺ Morning Exercise in New York XI, 2019

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课Ⅺ Morning Exercise in New York XI, 2019 -

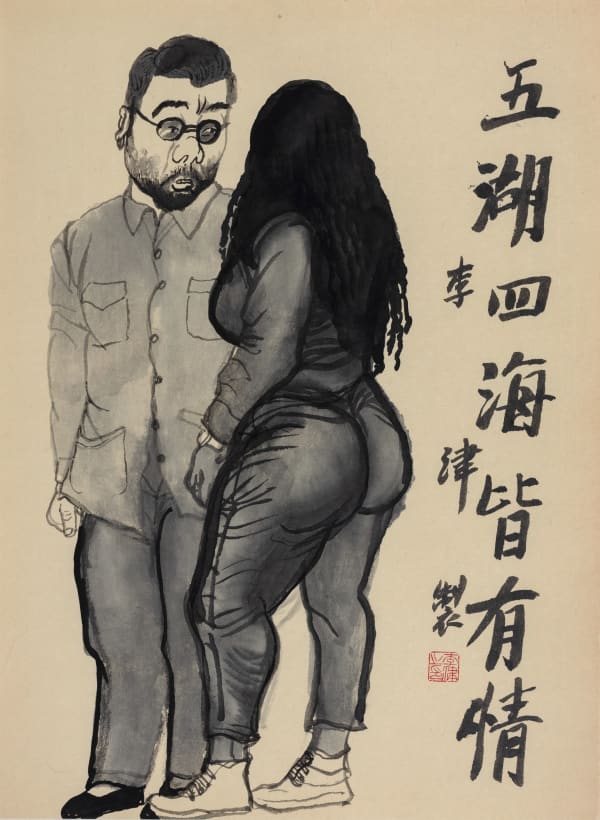

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课V - 五湖四海皆有情 Morning Exercise in New York V - Love is Everywhere, 2019

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课V - 五湖四海皆有情 Morning Exercise in New York V - Love is Everywhere, 2019 -

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课 - 好画家 Morning Exercise in New York - Good Artists, 2019

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课 - 好画家 Morning Exercise in New York - Good Artists, 2019 -

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课 - 纽约人 Morning Exercise in New York - New Yorkers, 2019

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课 - 纽约人 Morning Exercise in New York - New Yorkers, 2019 -

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课 - 纽约人 Morning Exercise in New York - New Yorkers, 2019

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课 - 纽约人 Morning Exercise in New York - New Yorkers, 2019 -

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课XII- 纽约街头 Morning Exercise in New York XII - New York Street View, 2019

Li Jin 李津, 纽约晨课XII- 纽约街头 Morning Exercise in New York XII - New York Street View, 2019 -

Li Jin 李津, Floating Rainbow #1 五彩缤纷的聚合 #1 , 2017

Li Jin 李津, Floating Rainbow #1 五彩缤纷的聚合 #1 , 2017 -

Li Jin 李津, Floating Rainbow #2 五彩缤纷的聚合#2, 2017

Li Jin 李津, Floating Rainbow #2 五彩缤纷的聚合#2, 2017 -

Li Jin 李津, Floating Rainbow #3 五彩缤纷的聚合#3, 2017

Li Jin 李津, Floating Rainbow #3 五彩缤纷的聚合#3, 2017 -

Li Jin 李津, Floating Rainbow #4 五彩缤纷的聚合#4 , 2017

Li Jin 李津, Floating Rainbow #4 五彩缤纷的聚合#4 , 2017